- Home

- Ben Masters

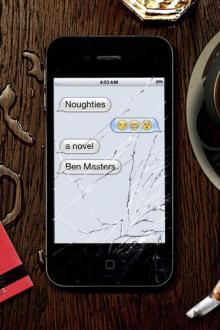

Noughties

Noughties Read online

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

Copyright © 2012 by Ben Masters

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Hogarth, an imprint of the Crown Publishing Group, a division of Random House, Inc., New York. Originally published in Great Britain by Hamish Hamilton, an imprint of Penguin Books Ltd, London.

www.crownpublishing.com

HOGARTH is a trademark of the Random House Group Limited, and the H colophon is a trademark of Random House, Inc.

Grateful acknowledgment is made to the following for permission to reprint previously published material:

Curtis Brown, Ltd: Excerpt from “Oxford,” copyright © 1938 by W. H. Auden, renewed, from Another Time by W. H. Auden. Reprinted by permission of Curtis Brown, Ltd.

New Directions Publishing Corp.: Excerpts from “Marriage” by Gregory Corso, from The Happy Birthday of Death, copyright © 1960 by New Directions Publishing Corp. Reprinted by permission of New Directions Publishing Corp.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available upon request.

eISBN: 978-0-307-95567-8

Jacket design by Ben Wiseman

Jacket retouching: Tal Goretsky

Jacket photographs: (table, glass) Tamara Staples, (matchbook, ashtray)

David Bradley, Photography, (cigarette on front cover) Maren Caruso

v3.1

For my parents

With thanks to Georgia Garrett,

Simon Prosser,

and Zachary Wagman

CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Epigraph

Pub

Bar

Club

And is that child happy with his box of lucky books,

And all the jokes of learning? Birds cannot grieve:

Wisdom is a beautiful bird; but to the wise

Often, often is it denied

To be beautiful or good.

—W. H. AUDEN, “Oxford”

Pub

“Ah mate.”

This is how it begins. This is how it always begins. Four flat characters sitting round a table, with our pints of snakebite, our pints of diesel.

“Ah mate.”

We contort our faces into gruesome grandeur, gurning with eloquence and verve: Scott with his question-mark nose, Jack with his inverted-comma eyebrows, Sanjay with his square-bracket ears. Nodding and grunting and twitching our legs, we clutch our carbonated weapons of mass destruction.

“Ah mate.”

My name is Eliot Lamb. I’m the one with the fierce mane. Utterly fantastic it is: blond, wavy, thick, and full of spunk. You can tell I’ve gone to a lot of effort with the old creams and unguents, but it is a special occasion after all: it’s our last night at university. I’ve even cultivated some designer stubble, sprinkled over my rosy face like Morse code, with all its dots and dashes. And if the code was readable it would go something like this: There’s a lot on my mind tonight, pal—oh such a lot—and things could get very messy.

We are in the King’s Arms, Oxford, rainy weekend eve, unfortunate travelers fumbling our way into the sticky crotch of a night on the lash.

“Ah mate.”

This is the end, beautiful friend, the end. Our university finale; the last time we’ll ever do this. The real world snaps viciously at our cracked-skin heels, groaning of jacket-and-tie, briefcase-headcase, hair-receding, tumble-dry mortality. I stare into the bottom of my pint glass and glimpse faint outlines of the infinite. I gaze into the abyss.

Sip, sip, chug: “Ahhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhh”—four pressurized valves released and relieved, letting off steam.

“I needed that,” blurts Jack, right on cue.

Scott: “Anyone else out tonight?”

(A droopy old man falters past. He wears the heady bonfires and dissident blossoms of the cool summer air, stirring fragrances of ale and tobacco.)

“I sent a loada texts” (that’s me). My tripwire legs are vibrating beneath the table, compulsive and anxious. “Some of the girls are coming in a bit,” I add judiciously. Rhyming nods of solemn approval. Jack traces his high-rise quiff just to make sure it’s still there.

Glug, glug, swallow.

The phone in my pocket chatters, clamping after my testicles with cancerous claw. I don’t reach for it. It’ll be Lucy.

She rang just before I came out, but I was a bit hesitant and evasive, needing to fix myself for the big night—picking the right shirt, nailing the hair, generally ogling the mirror in a you-talking-to-me-type fashion—and also being at an awkward place in my character development: I already have something pressing to face up to … something that needs to be dealt with, tonight. I do feel bad about Lucy though. She sounded, well, nervous; lost somehow. It was all the preambling that got in the way: Where are you, are you on your own, please don’t overreact to what I have to say. I was running late and that was valuable time spent already. Only now I have the feeling that it was something important … must’ve been … I mean, we don’t really talk on the phone anymore, and my promise to call her later seemed desperately inadequate. I should’ve just heard her out. But she was the last person I wanted to speak to, given my plans for tonight.

Maybe I’ll send her a text in a bit.

She doesn’t go here—Oxford, that is—not being the academic type. She’ll be making a lot of appearances though, whether haunting from the margins or dancing resplendent across my imagination, and she’s playing on my mind already.

“Ah mate.”

The King’s Arms is filled to spilling point. Students run rampant in red-cheeked naïveté. With military-front precision the place bares its insistent demographics: flowery thespians with lager for Yorick skulls; meathead rugby players (cauliflower-eared, broccoli-beard, potato-reared) floundering in homoeroticism; red-corduroyed socialites with upturned collars and likewise noses; bohemian Billies and Brionys, all scarves, hats, and paisley skirts; indie chics and glam gloss chicks; crushed-velvet Tory boys feigning agedness; pub golfers and fancy-dress bar crawlers; lads and ladettes, chavs and chavettes; and the locals, frowning at the whole motley spectacle. And then there’s us: the noughties. We are quotidian calamities; unwitting lyricisms; veritable Wordsworths out on the razz, lugging twentieth-century regret on our backs.

How to convey the gang to you … Scott, Jack, and Sanjay … Well, I like to buttonhole people; fasten them in nice and tight wherever I see fit and wait for the holes to sag. The buttons begin to shuffle and slide, impatient with the restriction. And then—the hold worn, no longer adequate—they break free. Excuse the ready exchange of metaphors, but as Augie March says, there is no accuracy or fineness of suppression; if you hold one thing down you hold the adjoining. My style is to hold everything down, as firmly as possible, and hope that only the most vigorous stuff rises.

So, there’s Jack, still my best mate (I think) and clown extraordinaire. Right now he’s clenching a pint of Stella and wearing a white-collared blue shirt (sleeves rolled, top three buttons undone), flashing a hairless chest with each flap of the loose collar, his shortish brown cut molded to aerodynamic specifications. Next to Jack is Scott, rocking a sprawl of auburn without styling gel (he’s private school and they don’t really do hair product like us staties). Scott’s drinking Kronenbourg and chancing a pink shirt. He’s bigger than the rest of us, being a college rower and rugby player, but he has the softer disposition, his various insecurities taking the edge off his muscles. Jack and

I have affected occasional gym regimes ourselves, though we never actually change shape or size, clinging to our coat-hanger frames and the self-assuring consolation that “girls don’t like big men.” They don’t. Muscle freaks them out. Still, we bought a barrel of protein shake at the start of our second year, hoping it might prove the key to the kind of rapid muscle development we felt we deserved. I was happy just mixing the potion in with a glass of milk after each workout, while Jack all-out binged on the stuff, sprinkling it on his cornflakes, dipping crisps and chocolate bars, pouring it into his bedside glass of water, even layering it on top of his toothpaste. Naturally our bodies stayed stubbornly put: no tightening of skin, no swell of veins, no progression in shirt size. Don’t get me wrong, we’re not runts or anything … just bothersomely average. And finally there’s Sanjay (Stella), wearing his black Fred Perry with the white trimming. It’s his “lucky” shirt, though I can’t testify to the accuracy of the appellation. If it does attract the fairer sex it’s certainly not working its voodoo tonight: our table is demonstrably cock heavy. Sanjay has a little blinking tic going on. Every now and then he is able to shake it off, but as soon as you remind him (“Hey, Sanj, I haven’t seen you do the blink in ages”) it returns (“Oh, for fuck sake” wink wink). You want to know what I’m wearing too? Black jeans, on the skinnier side of slim fit, and a blue and white check shirt. Stella.

We’re over at the quiz machine, slurping our student loans and tossing shrapnel into the slot. Gather round …

Q: In Brideshead Revisited, what is the name of Sebastian’s teddy bear?

A: Paddington B: Rupert

C: Aloysius D: Baloo

Drink while you think.

“C’mon, Eliot, you do English,” says Jack.

“Did English. I’m finished now, ain’t I?” I protest. “How the fuck should I know anyway?” Jack, a physicist, has always wondered what exactly it is that I do know—literature as an academic pursuit being entirely mysterious to him—and is looking at me doubtfully. The only social utility of my subject that he can make out is its occasional propensity for sparking progress on quiz machines, as well as select rounds of University Challenge. “But yeah,” I add. “It’s definitely Aloysius.”

English: I’ve served three years. Pulling all-nighters over weekly essays, arguing indefensible points with unswerving commitment, and defying all common sense with consistent ill-logic, I’ve completed my subject. English. I’m nearly fluent now, mate. But what next? Back to Wellingborough I guess. (I feel it closing in like an obscene womb, pulling me into its suffocating folds …) And then what?

“Fuck yeah,” shouts Jack, selecting the correct answer.

There goes my phone again. Lucy.

Why did I have to mention Lucy so early on? I promised myself that I wouldn’t. It makes things so much harder than they already are. Perhaps that’s why I was reluctant to talk to her earlier. Too late now—she’s gone and hooked herself into the night’s narrative. It’s fitting, I suppose … she was with me at the start of this Oxford story, and now she’s making her presence felt at its end.

Lucy was my secondary-school sweetheart. She’s a year younger than me and therefore, in school terminology, falls under the ominous label of “The Year Below,” such distinctions being vital in the zitty adolescent universe. We hooked up the summer before I went down to Oxford, three years ago now, and fast-tracked our way through the various steps of romantic training—an eight-week intensive in Sex Theory and Love Management.

I remember those early days vividly. She used to leave pieces of herself in the bed for me to commune with through the night: bittersweet surprises, proof of our love and decay. She’d douse the sheets in her secret smells, deftly scattering personal trimmings under the duvet and atop the pillow: long brown hairs like fragile question marks, arranging themselves into the broken outlines of a sketch; minute bits of skin like the baubles on a damp towel; all those mysterious stains and pools of our concentric love.

On my last night at home—my final night before the horror-movie transformation into lager-lube student—everything still felt so new. There we lay, fallen creatures. The fledgling months, ah—

“Same again, mate?” asks Jack tentatively. I tilt my glass and soberly evaluate the contents … nearly empty.

“Yeah, cheers.” I drain the leftover. Jack’s heading off to the bar.

Where was I? Yes, the fledgling months … they’re the sweetest, are they not? Explorations into the unknown and no turning back. Discovering new creases and folds, hidden moles and scars, we marked up the cartography of each other’s bodies. Our greedy hands learned to the touch, molding and impressing, leaving imprints for rediscovery to be fitted into again and again. We puzzled over our astonishing elasticity, pioneering to establish ourselves.

Oh Lucy …

Not that everything was so profound on my “farewell” night. There was, for instance, the sexed-up playlist singing instructively in the background with all its hints and prompts: Vandross, Marvin, Prince, Boyz II Men, Bazza White, Sade … which must have had her thinking how white and unsexy I was in comparison, and how small my— no, no, no! You can’t say that kind of thing! All it had me thinking of, on the other hand, was my parents’ vinyl collection, forcing involuntary images upon me that I just didn’t need, that I just don’t ever need, believe me: I do not want to have sex with my mum. And Dad, put that away RIGHT NOW! Luckily Lucy did not take the lyrics as a direct representation of my intentions (“You want to do what to my what?,” “You’re gonna spray your what all over my where?”), though there was considerable calamity when the iPod malfunctioned and switched of its own accord to Reign in Blood by American heavy-metal outfit Slayer (how’d that get on there?). I leaped from my bed to the thrashing riffs and commando-rolled across the floor, my buttocks flashing pale like two miniature moons, groping after the disobedient audio player. Eventually the sound track played itself out (coming in around the thirty-minute mark, which I have to admit was wildly ambitious on my part) and we snuggled down on the embarrassed bed.

Lucy peered up at me with inquiring eyes, her naked figure censored by the shelter of my side. Her dark brown hair, with its subtle sheen of ocher, fanned out over the pillow like an upended curtain tassel, and her heavy tan bolstered the already potent comedy of my fridge-white skin. I’m like a man wrapped in printer paper to look at in the buff. Weak-kneed from the cold scrutiny and paranoia that swallows you whole after orgasm, I was glad to be lying down.

“I don’t want this summer to ever end,” she whispered.

This was my cue. We’d begun our relationship under the promise to split come summer’s end, when I would leave for Oxford. Not my idea. Lucy, with her extra year left at school, thought it gallantly realistic and (mistakenly) what I wanted to hear. But then we were ignorant of adult complication. I begrudgingly accepted our relationship’s small print, secretly ambitious to violate this most restrictive clause. I didn’t care about rocking up to uni an available man. I really didn’t. I’d begun to revel in my not-for-sale status; in our private culture for two.

“But I guess it’s time,” she concluded, a lilt of martyrdom in her voice.

I would be leaving the next morning to become, as Fitzgerald’s Gatsby puts it, “an Oxford man”—whatever that means. The ruffled bed was surrounded by boxes brimming with my stuff—books (battered Dickens, partially read Shakespeare, unthumbed Joyce, Eliot, Wordsworth, Keats, straight from the uni reading list), DVDs (Partridge, Sopranos, Curb), clothes (flimsy tees and skinny jeans), CDs (the Stones, Leonard Cohen, Talking Heads, some old-school hip-hop, Radiohead, Arctic Monkeys, D’Angelo). I stroked the top of Lucy’s inside thigh—that part of a girl’s body so exquisitely smooth and soft it feels like you’re about to slip off the earth.

“Suppose we don’t want to break up,” I risked.

Her eyes widened as she pulled closer, and I felt a flutter of clichés coming over me.

“What do you mean?”

&

nbsp; “I don’t really want to end this.”

“No, neither do I.”

“Will you come visit me next week?”

“Of course.”

I chewed on the inside corner of my mouth, creating that subtle metallic taste of silent concentration. I tried forecasting how the turn of the conversation might impact our futures, how it would actually unfold, but the vision was limited by the soft warmth of the body next to mine.

“Shall we just stay together then?” I asked.

Lucy has an adorable habit of nodding along in conversation, regardless of the content—a kind of ready agreeability—but this time it seemed thrillingly conscious: “Yes … I think we should,” she said.

“Awesome,” I said (a sublime note to end on, I thought).

“Great.”

The wallpaper in this joint is waxy; smoke-stained from times of yore. It’s lumpy and tactile, like a golden-brown resin caked over the top of dead insects: worm circles and cockroach grids, the patterns of nausea. The furniture is despairingly ad hoc: drippy tables and diverse races of chairs rubbing up against each other; tall and thin, short and fat, sunken, bony, flappy and slappy, and all else in between. These death-row seats, those unholy pews, don’t so much nuzzle our buns as butt them away.

“It’s proper muggy in here,” says Jack with an air of constraint, like he’s trying to dispel an unacknowledged awkwardness.

“Is it,” I concur.

I’ve been dreading this night for three years now, all of which have been spent looking the other way, hoping it would never come. But it finally has, with its big hairy balls dangling in my terrified face: the end of my student “career” (don’t you dare laugh!) as I pass into— no, can’t say it … mustn’t say it.

Immediately to our right stands a harem of females, pretty, but clearly underage. It’s easier to sneak in on busy nights like this. They’re getting chatted up by some smarmy postgrads who should know better. Trouble is, they know they can’t do any better, punching above their weight and below the law.

Noughties

Noughties